AAA conducted a study to determine how effective a “learn as you go” approach is for drivers new to ADAS systems. How does knowledge of ADAS develop over time with no outside influences like a demonstration or a user’s manual to shape it? To answer that question, AAA took 39 drivers with no previous experience with adaptive cruise control (ACC) and tracked how their knowledge developed throughout six months of use. Compared to an earlier study where drivers had direct instruction, AAA found that learning through firsthand experience only results in misconceptions about ADAS functionality and limitations.

“This research suggests that today’s sophisticated vehicle technology requires more than trial-and-error learning to master it,” said Jake Nelson, AAA’s director of traffic safety advocacy and research. “You can’t ‘fake it ‘til you make it’ at highway speeds. New car owners must receive training that is safe, effective, and enjoyable before they hit the road.”

Methodology: Participants & Testing

AAA studied 39 experienced drivers between the ages of 25 and 65 to understand each driver’s self-taught perception of ACC’s functions and purpose. To truly explore how knowledge of ADAS forms, all were drivers whose first exposure to ACC was no more than six weeks at the start of the study.

Written Portion: Determining Driver Competency

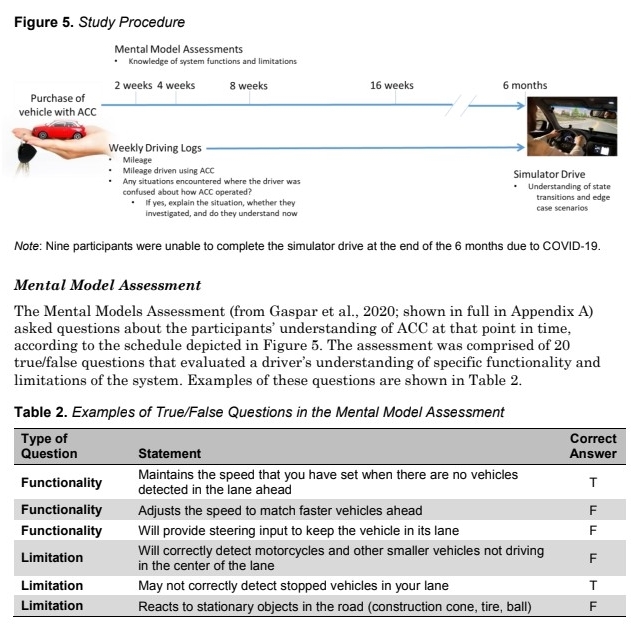

Throughout the six-month study, AAA gave the participants six different mental model assessments to measure knowledge and confidence levels. To test this knowledge, AAA came up with a list of statements for drivers to mark as true or false. The chart above shows some statements and whether the statement tested the driver’s understanding of ACC functions or limitations. After every true or false question, drivers rated the confidence of their answers on a four-point scale. Participants were also given scenarios where they attempted to predict the reaction of ACC.

AAA provided a questionnaire where drivers reported how many miles they drove each week and how often they used ACC. When they encountered scenarios like a fast merging vehicle or a construction zone, the drivers reported those instances and any confusion they ran into with the system.

The Simulation: Determining Driver Performance

At the end of the study, drivers participated in a simulator session representative of a 2019 Toyota RAV4. The simulator mimicked real-life situations to test their practical understanding of ACC. Several scenarios were incorporated; one scenario involved an object in the middle of the road, a construction cone indicating a lane closure. The vehicle in front of the driver then merged to reveal a work zone in the right lane ahead. How the driver responded and their response time was measured. The drivers who responded correctly took control, slowed down, and safely switched lanes.

Limits of The “Self-Taught” Approach

Four groups emerged at the end of the study. AAA grouped together those of similar performance and like-minded drivers to study learning trends and results.

Improved Knowledge Groups

- Group 1: High knowledge and high confidence.

- Group 2: High knowledge but low confidence.

Groups 1 & 2 both tested high in knowledge and improved their understanding of ACC. However, AAA observed that the improvements were primarily due to the driver’s knowledge of ACC’s limitations rather than knowledge of the function. Despite learning more about ACC through regular use, even this improved set of drivers failed to achieve the same level of understanding compared to another group of drivers that received short but extensive instruction on the system in a previous study. The same questions were used in both studies to create an accurate comparison.

Lower Knowledge Groups

- Group 3: Low knowledge and low confidence.

- Group 4: Low knowledge but high confidence.

Groups 3 & 4 tested low in knowledge and failed to grasp the function of ACC, performing poorly overall in both the mental model tests and the simulation at the end. Despite the title of “low confidence” for Group 3, they still demonstrated higher confidence by the end of the study, though not as high as Group 4. The increase in confidence was not reflected in their test scores since both groups performed worse than when the study began. Most concerning is Group 4, who thought their time behind the wheel gave them expertise even though they demonstrated the least amount of knowledge according to this study.

Overconfidence is never a good mindset for approaching ADAS systems. A previous AAA study shows that ADAS systems require constant vigilance. In 4,000 miles of clear highway driving, there were 521 total events of ADAS technology not behaving how it was intended. In other words, every eight miles, some type of error would occur. Even when ADAS systems are not presented with edge-case scenarios, the driver must be prepared to take back control.

Misconceptions That Formed

The results showed many of the self-taught drivers had a better understanding of the limitations of ACC, but gaps in knowledge emerged. Hands-on experience with the technology over a period of six months didn’t educate drivers correctly on ACC functions and limitations. By the end of the study, some drivers falsely believed that ACC operates in all weather conditions, provides steering input, and will react to stationary objects in their lanes like construction cones or other obstacles.

For drivers who only learn through experience, the correction might come too late. Especially if the lesson that corrects these misbeliefs is a car accident that causes harm to the hands-on learner.

“Our research finds that drivers who attempt the ‘self-taught’ approach to an advanced driver-assistance system might not fully master its entire capabilities,” said Dr. David Yang, executive director of the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. “In contrast, drivers who have adequate training are able to effectively use the vehicle technology.”

Looking Forward: Exploring The Learning Process

AAA suggests finding the benchmark of knowledge drivers need before they can safely and effectively use ADAS technology. AAA recommends that researchers, automakers, and government agencies work together to understand better how drivers interact with ADAS systems and how their knowledge changes over time. It’s also essential for all parties to work towards a standardized nomenclature for ADAS technology.

“Consumer confusion is a serious issue,” said Maureen Vogel, Director of Communications for the National Safety Council. “We know that our cars cannot operate safely without us, so it is important to avoid certain terminology – autopilot, for example – that could lead drivers to abdicate responsibility and trust the machine to operate independently of the driver.”

AAA noted another key takeaway: the differences across the board in the mental models among individuals. Due to the limitations of sample size and COVID-19 restrictions, a larger sample size in the future would be vital to understand better the individual difference in driver performance and mental models. The complete AAA study, including a comprehensive 40-page breakdown report, is available here.

“We need to ensure we keep the consumer at the front of the mind when we’re designing a system,” said Greg Brannon, Director of Automotive Engineering and Industry Relations at AAA. “It’s very easy to get caught in the trap of technology for technology’s sake. We need to make sure that what we are building is actually helping the consumer.”