“With remote assistance, the automated driving system recognizes that something is different and sends a request to the remote assistant for guidance. The remote assistant lets the automated driving system know how to proceed without taking over and driving the vehicle. The remote assistant is just providing information back to the automated driving system to facilitate its trip continuation.”

Darcyne Foldenauer, director at the Automated Vehicle Safety Consortium.

Citation: Figures below reprinted with permission from AVSC Best Practice for ADS Remote Assistance Use Case, AVSC-I-04-2023.© 2023 SAE ITC.

Real-Time Guidance

When a vehicle equipped with an SAE Level 4 automated driving system (ADS) operating without a driver encounters a novel or complex situation it cannot decipher, what does it do next?

It taps into what’s called remote assistance for information and advice from a human remote assistant before it proceeds on its own. Remote assistance in this context falls under the umbrella of remote operations.

More specifically, the remotely located human assistant provides real-time guidance to the ADS-dedicated vehicle (ADS-DV) in scenarios that exceed its design capabilities to facilitate trip continuation. This is according to SAE J3016, Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles, published by SAE Industry Technologies Consortia (SAE ITC).

What Is Remote Assistance?

Another way to think about it is that remote assistants improve operational efficiency. Their efforts help fleet operators avoid the cost and time delay of someone driving out to an ADS vehicle to get it unstuck when it does not know what to do.

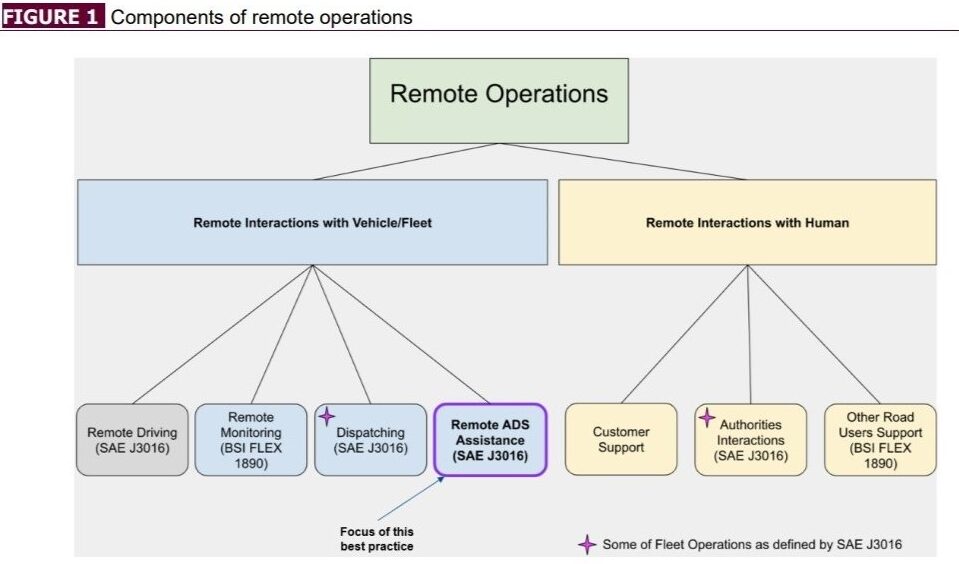

As described by SAE ITC, remote assistance is not remote driving. Remote driving, defined as remotely performing the dynamic driving task (DDT) or fallback performance, entails a human operator taking control of a vehicle remotely and maneuvering it from afar using cameras, lidars, and other sensors.

Nor is it dispatching (i.e., the selection of destinations or trip initiation timing), even if the same person performs both remote assistance and dispatching functions. Nor is it remote monitoring or customer support.

Figure 1 below shows the components within remote operations, distinguishing remote interactions with vehicle/fleet from remote interactions with a human. It encompasses various functions, such as remote driving, remote monitoring, and dispatching.

Remote Assistance vs. Remote Driving

While the difference between remote assistance and remote driving may seem straightforward in a general sense, there is a lack of clarity around the parameters of remote assistance, which is why the Automated Vehicle Safety Consortium (AVSC) stepped in to provide a new best practice.

“We saw a need for defining what it is, what it is not, and how to implement it,” said Darcyne Foldenauer, director at the AVSC. “This best practice, AVSC Best Practice for ADS Remote Assistance Use Case, offers ADS manufacturers, developers, and fleet operators guidelines for understanding the functionality of remote assistance in SAE Level 4 and Level 5 ADS-DVs, including defining the kinds of events that could trigger remote assistance.”

“There is a lot of confusion regarding the role of remote assistance,” said Philip Koopman, associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University and respected AV thought leader. “This AVSC best practice is both useful and timely for the industry.”

Workstream Categories & Public Confidence

AVSC best practices fall into three “workstream” categories: test and validation, interaction, and data. Each is intended to build upon or support the other. The guidelines can be applied to any vehicle, ADS architecture, or commercial use case.

The mission of the AVSC is to accelerate best practices into global standards focused on the safe development, deployment, and fleet operations of automated driving system dedicated vehicles.

“It is our goal to engender public confidence in the safe operation of SAE Level 4 and Level 5 light duty passenger and cargo on-road vehicles ahead of their widespread deployment as well as to build public trust and acceptance of automated vehicles as a safer and beneficial form of transportation,” Foldenauer said.

Requesting Confirmation Before Acting

This new best practice, also called AVSC-I-04-2023, establishes the framework around remote assistance, clearly defining it as a remote human advisor and offering ideas for training that person, Foldenauer explained.

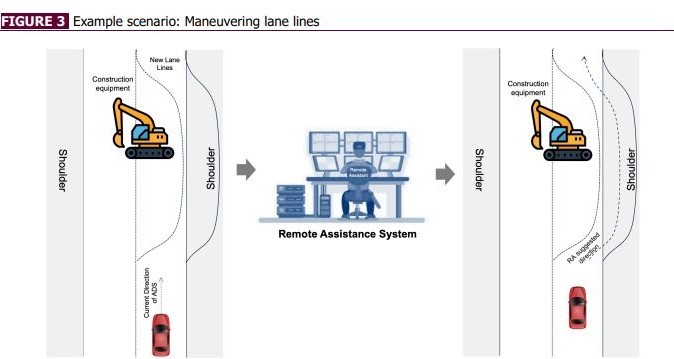

At a high level, it describes how to implement remote assistance, including collecting data from the vehicle’s sensors, defining triggers, and outlining possible responses.

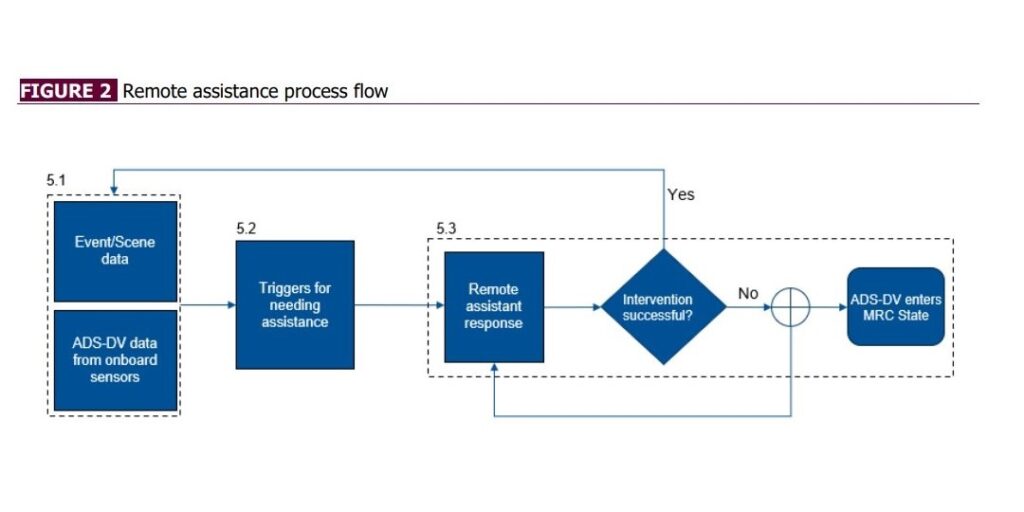

“Assume an AV is driving along, and it detects an unexpected lane blockage caused by construction equipment,” Foldenauer continued, offering an overview of an example detailed in the best practice. “Maybe temporary lane lines have been sprayed on the road due to construction, extending onto a shoulder, and the ADS recognizes this as unusual – where the vehicle is not normally permitted to drive on the shoulder.”

“A remote assistant might connect during a trip to help the vehicle gain confidence in its understanding of the situation,” Koopman added.

In Figure 3 above, the ADS is navigating on the road when it detects an unexpected lane blockage caused by construction equipment.

This type of complex road situation, as outlined by Foldenauer, would trigger a call to remote assistance, in which the ADS would collect data from its sensors and send it along to the human assistant for more information or advice. The remote assistant would look through the data from the camera and other sensors and decide on a response.

“For example, maybe the lane markings indicate the ADS should drive on the shoulder, but the ADS wants to obtain confirmation before doing something that isn’t normally permitted by the road rules,” Foldenauer said. “The remote assistant would view the data involved and communicate to the ADS that it’s acceptable to proceed. The ADS would then follow the lane markings onto the shoulder and around the construction.”

Figure 2 above demonstrates a high-level process of implementing remote assistance which includes:

- Step 5.1: Vehicle data collection.

- Step 5.2: Triggers for needing assistance.

- Step 5.3: Remote assistant response.

Safety Critical vs. Non-Safety Critical

An important distinction is remote assistance is non-safety critical, while remote driving is safety-critical. Remote assistants do not perform safety tasks – i.e., they are not supposed to notice something dangerous and intervene.

“This AVSC document clarifies that remote assistance is not responsible for safety-critical functions, which means the vehicle itself retains full responsibility for safe operation,” Koopman said.

Because remote assistance is about improving operational availability and not safety, calls to remote assistance should not be seen as a safety problem. According to Koopman, frequent calls might be a concern for economies of scale but not safety.

“The way this could become a safety problem is if the autonomous vehicle does not call for remote assistance when it should have done so and is driving confused without realizing it,” he said.

What AVSC-I-04-2023 Accomplishes

Foldenauer noted that AVSC-I-04-2023 adheres to the SAE ITC J3016 definition of remote assistance – commonly referred to in the United States – and can be used alongside a manufacturer’s local rules, regulations, and standards, which she explained sometimes differ in definitions.

“When we write these best practices, we try to keep them very open so that anyone can use them, whether they’re a manufacturer, a developer, or a fleet operator,” Foldenauer said. “It is left up to each organization to determine which regulations they need to follow.”

Regarding the most important thing the AVSC feels they accomplished with AVSC-I-04-2023, Foldenauer pointed to AVSC’s creation of a framework that integrates remote assistance within the context of an ADS. “We’ve defined the functions, the tasks, and their role in safeguarding performance, efficiency, and safety,” Foldenauer said.